STRANGERS IN A STRANGE LAND

By Suzanne Ahearne

Special to The Globe and Mail, June 20, 1998

TRAVEL cover story and photographs.

Japanese Sumo wrestlers and their media entourage take a 14-hour power tour of photo-ops, souvenir shops and gourmet meals through the Rocky Mountains, before flying to Vancouver for the Sumo Canada Basho. I trailed them in a rented car and slipped onto their tour bus to chat when their security guards were occupied.

Futatsukuni has four cameras, all of which he tucks into the sash of his kimono. The low-ranked, nonsalaried sumo wrestler, in Canada earlier this month for a sumo tournament at Vancouver’s Pacific Coliseum, notes that he may never have a chance to visit this country again. And he is determined to capture on film the Canada of his imagination.

It is a Canada he sums up in two simple words: “mountains” and “wildlife.”

Like the 63 other sumo wrestlers, or rikishi, making a 14-hour power-tour through the Canadian Rockies days before the tournament, Futatsukuni sees these mountains not just as the essence of Canada. To him, they are the stuff of wilderness itself and it’s just as well he has so many cameras. The tour’s pace allows no time for quiet contemplation. For this, he must wait until his prints come back from the one-hour lab back in Tokyo.

The rikishi’s expectations of the Canadian wilderness have been fueled by Japanese TV specials, magazine stories and the personal photo albums of family and friends, likely based on their own similarly frenetic forays to these mountains. But their expectations aren’t likely to be dashed. Nature has served up a postcard-perfect morning, and there are 31 tour organizers, guides, translators and security people accompanying the rikishi to make sure nothing goes wrong.

To boot, there’s Japan’s Asahi Broadcasting network. It paid royally for the TV rights to this Rockies trip and to the tournament, or basho. Big money is riding on this trip looking good on film, and the network has stage-managed a breathtaking itinerary.

In the Roots store in Banff, Akebono flops down on a couch after buying his three-week old daughter a tiny outfit. The 6-foot-8, 511-pound Hawaiian asks the crowd of fans gathered around him: “Why are there so many Japanese here?” Everyone laughs, including the gang of Japanese media congregating around him. Apparently, this kind of reception was the last thing the rikishi expected in this little shopping oasis in the middle of the wilderness.

And what of the wildlife photo-ops? Shikishima has been videotaping about 10 kilometres of the stunning, snow-capped mountains between Kananaskis and Banff from the window of the high-riding charter bus, when he figures he ought to replace the battery. Then he sees a moose at the side of the highway. “By the time I got the battery back in, I only got its back end, very small, running away,” he says. The same thing happens again later, this time with a coyote. “I’m glad I saw it, but, of course, I regret I didn’t get it on tape,” says the disheartened rikishi.

Such animal sightings, seen by only a few and blurred by the speed of the tour bus, are like phantom apparitions: barely tantalizing and yet strangely satisfying to those who want to believe.

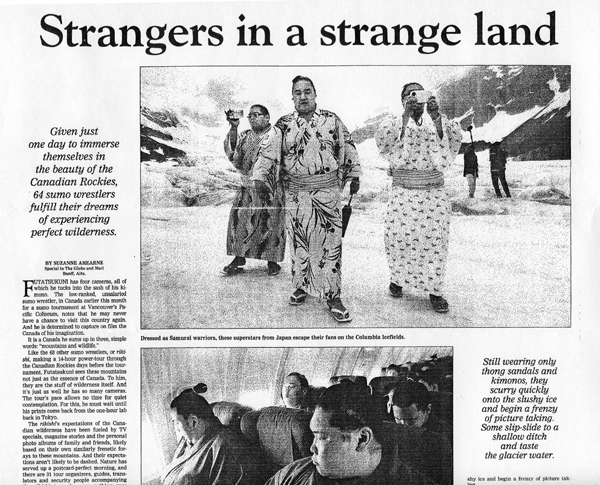

For the gastronomic pleasure of the world’s biggest eaters, two of the grand old dames of Canadian luxury—the Banff Springs Hotel, for lunch, and the Chateau Lake Louise, for dinner—have been called upon to provide the best in Canadian cuisine. It just so happens that the Chateau also has one of the most famous photo backdrops on its front doorstep. The view of the Victoria Glacier and of the parallel mountain slopes that slide into the emerald lake is known throughout the world. And it is the image that, more than any other, the media most want to take home with them. To have pictures of their beloved rikishi standing here in the lavish attire of the 12th-century Samurai warriors…well, it was like consecrating already-holy ground.

They want the image so badly, they postpone lunch until they get it, leaving the rikishi exactly 40 minutes to wolf down a buffet lunch and be back on the bus to be whisked away to the Columbia Icefields. The advertisements for Brewster Snocoach Tours—whose all-terrain vehicles take tourists up the big dirty-white tongue of ice to glimpse the untouched 325 square kilometers of ice beyond—have the perfect hook: “Want to see Heaven frozen over?” Yes. Yes. Sixty-four times, yes.

The whole day has built up to this. By the time the wrestlers get up here, they’ve been in and out of a bus for the better part of seven hours. Snow clouds are starting to obscure the horizon; the tour guides tell them to be back on the bus in 15 minutes.

Still wearing only thong sandals and kimonos, they scurry quickly onto the slushy ice and begin a frenzy of picture taking.

Finally, they ignore the press and pose only for themselves. Futatsukuni pulls out all four of his cameras. Some of his more agile mates slip-slide to a shallow ditch and taste the glacier water. They take pictures of each other with the frigid water dripping from their cupped hands. Some take off a sandal and feel the ice. They take pictures of their bare feet.

The day has no slow dénouement.

By the time the coaches are at the bottom of the glacier, the mountains are closed off, and grey descends. While the rikishi change buses, several of them huddle together under the half-cover of the bus shelter for a quick smoke. Then they’re back in the Snocoaches... and gone. Within a few minutes of their departure, the snow hardens into a pelting rain.

It is as though nature has relished the chance to fulfill their dreams of the perfect wilderness—and then, with nothing more to show them, has resumed its stolid, grey indifference.